Utopia in Tennessee: Part 3, Political Utopias

- lvenegas13

- Oct 12, 2025

- 12 min read

Updated: Oct 13, 2025

This is the third installment on Utopias in Tennessee, this time on Political Utopias. In previous posts we looked at Religious Utopias and Black Utopias in Tennessee, and in this third and final segment we will look at Political Utopias of Tennessee’s past and where they are today.

I mentioned earlier that the movement toward starting Utopias in the US was often a blurring of ideals, such as religion, politics, feminism, environmental, and agrarian. It’s a gross simplification to say the following settlements are solely political utopias when they often included other principles, but at their heart it was societal disenfranchisement which led the individuals of the colonies to gather. Political utopias in the US were started by reformers fighting for those struggling to make ends meet or being crushed by poor working and living conditions. In books and newspapers, they inspired hope, and some were radical enough to try to make the concepts a living reality. However, philosophizing about a utopia and actually creating one are quite different things, and proved much more difficult than could have been imagined. Here are the stories of two fascinating political utopias from Tennessee’s history, both inspired and created by famous writers with their own ideas of Utopia: the Rugby Colony and the Ruskin Collective.

THE RUGBY COLONY: GENTEEL CHRISTIAN SOCIALISM, 1880-1887

1331 Rugby Parkway, Rugby, TN 3773

Visitor Centre Hours 9-5 EDT Thur/Fri/Sat, Noon-5 Sun.

Tours 9,11,1,3 EDT Sun 1 &3 EDT.

In the beautiful country of the upper Cumberland Plateau, amidst river gorges and forests sits an English Victorian village that looks lost in time and certainly out of place. One road runs through it, and in no time at all you’re enveloped by 65 or so of the original colony’s restored buildings: lovely homes, a museum, a fascinating cemetery, one of the quaintest churches in the state, and one of the most famous libraries in the nation. This picturesque community, recognized by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, is a gem, and behind the town is a fascinating story of how it came to be. As with other utopian societies there was a dream, drama, and tragedy, but there was also triumph in saving this community when so many others were lost to time.

In Victorian England there were a handful of authors who were famous not just for their storytelling but for their ability to insert social commentary into their works. Thomas Hughes was one of the best and he was many things: a lawyer, judge, and a politician with socialist leanings. His 1857 semi-autobiographical book “Tom Brown’s School Days” was immensely popular and a veiled commentary on Victorian Britain's attitudes towards society and class. Among many things this Christian socialist reformer was deeply involved in the creation of early trade unions and cooperative businesses. He was a self-made man because he had to be: at the time the practice of primogeniture dictated that the eldest son would inherit an estate. This left other children like himself with few choices for acceptable employment or at the mercy of the inheritor. Hughes saw his fellow second sons often struggling to create lives for themselves, denied status, and depressed by the limited choices before them. So, Hughes began to dream. If Victorian society was too rigid to allow these men to flourish, then why not create a colony in America where the rules didn’t apply? He knew that the US was having its own problems at the time and that people there were voicing frustrations around their choices. The Long Depression of 1873-79 caused the unemployment of thousands of former industrial workers in the UK and the US. He believed that wishing to own land and creating a life for oneself while living cooperatively with others were dreams that would appeal to both British and American societies. Based on the ideals of his best-selling book, he set out to make his utopia a reality.

As it happens, Franklin W. Smith, a wealthy Boston merchant, abolitionist, and reformer was already at work on a similar idea. He wanted to "divert workers from surplus in manufacturing to Tillage of the Earth—the basis of all industries, and the primary source of all wealth." Soon the Boston Board of Aid to Land Ownership went to work to find the perfect land for a settlement. When the Cincinnati Southern Railroad planned a line to the Cumberland Plateau he saw his chance, and in 1878 he gazed upon the beautiful land in Tennessee and began rounding up investors. His idea was to create a resort, where guests would be lured by the beauty and want to buy land there. Hughes and Smith knew each other, and Hughes jumped at the chance to have the land for his dream. But soon it became clear that there were fundamental problems with how each saw the future of the settlement. Hughes refused to put money towards a resort, he was focused on a Christian socialist society, and soon after this Smith divested himself of the project, leaving Hughes to create the town he wanted. It was a rocky start, and these weren’t the only problems the colony would have.

Hughes named his utopia Rugby after the beloved school he attended in the UK. At the heart of Rugby was still a hotel, which would be the lifeline of the colony, but there was also a sawmill, general stores, a drug store, and dairy and butcher shops. Since we’re talking English gentry, there would have to be refined pursuits to pass the time. There would be plays and meetings of literary societies, lawn tennis, and regular games of rugby. The first public lending library in the nation was established with 7,000 books donated from Europe and the US (and of course Tom Brown’s School Days was included) and newspapers started, the Rugby Gazzette and the Rugbeian. Hughes insisted that a church be constructed that would serve the Christian denominations of all who lived there, and beautiful homes were built and filled with furniture and antiques. But this was meant to be a cooperative that made money, so land would need to be converted to farms and a cannery created. At the height of its glory Rugby had 350 members in its community, and while Hughes himself only spent a month or so a year there, his mother, brother and niece made the colony their home. (His wife seems to have refused to come, believing the settlement to be a folly and not too happy with the idea of roughing it.)

“We’re about to open a town here to create a new center of human life in this strangely beautiful solitude center in which, as we trust, healthy, hopeful, reverent or in one word ‘godly’ life shall grow up from the first, and shall spread itself, so we hope, over all the neighboring regions of the southern highlands.” – Thomas Hughes, October 1880 at the dedication of Rugby.

But this is not the tale of a successful colony, so where did it go wrong? For starters, the soil was poor, a real challenge for any farmer, let alone factory workers and English gentry who had never toiled a day in their lives on a farm. And there was another problem: The railroad line was eight very long miles away through rough country, not exactly convenient for either taking goods to northern markets or for attracting business. If that wasn’t bad enough, many of the land deals that Smith had orchestrated turned out to be worthless, as the original settlers to the area refused to give up their land to the Rugbians, so the colony’s actual size was thousands of acres less than what they had originally supposed it to be. It may also have been a challenge mixing Appalachian settlers, the northern blue-collar factory workers, and a genteel foreign class. I can only imagine the reaction of the working-class Americans to seeing smartly dressed ladies and gentlemen gleefully chasing balls when there was so much work to be done! Throw in a drought, a tragic typhoid epidemic, and two fires that destroyed the inn, and by 1889 most of the settlers had left or died.

Hughes was apparently heartbroken and did not give up hope that Rugby could someday be successful. In 1896 he wrote the remaining settlers saying, ‘I can’t help feeling and believing that good seed was sown when Rugby was founded and someday the reapers, whoever they may be, will come along with joy bearing heavy sheaves with them.’ In fact, his dream did come true in a way. The town survived, and by 1966 the descendants of the original settlers, friends, and residents had committed to preserving the history and structures of this wonderful site. Today Historic Rugby, Inc. has done a marvelous job of saving the town as a living community and historic district with a museum and many planned events throughout the year. Nineteen original buildings remain, including the 1887 Christ Church Episcopal with its original pews, lamps and stained glass, the Thomas Hughes Library with its original books, the School House/Museum, and Hughes’ 1882 home Kingstone Lisle. Autumn is an especially beautiful time to enjoy the town, take a hike, and maybe throw in a haunted tour! It may not be a socialist enclave now, but it has found success as a voice to the history of the British Isles in Appalachia.

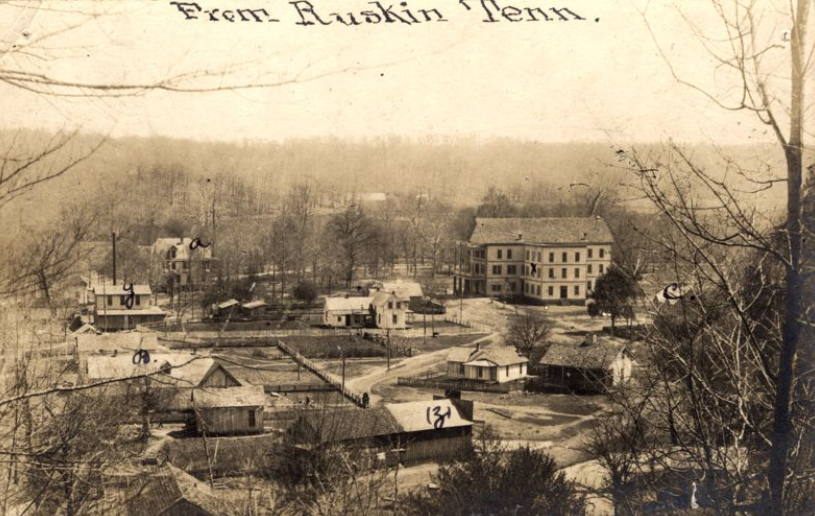

THE RUSKIN COLONY: THE FIRST MARXIST COLLECTIVE IN THE US. 1893-1899 in Dickson County, TN, then 1899-1901 in Ruskin, GA , (AKA The Ruskin Co-operative Colony or Ruskin Commonwealth Association)

2803 Yellow Creek Rd., Dickson, TN 37055

615-740-5502

Request a tour via the Contact page.

It may come as a surprise that not a hundred years after the birth of our country there were US citizens who wanted a more communist ideal! But social forces were at play, and the aftermath of the Civil War as well as the effects of the Industrial Revolution meant that not everyone was having an idyllic existence. The Progressive Era was a time when political and social reformers expressed great concern over labor conditions, poverty, the state of urban living, political corruption, the concentration of wealth in a few families and women’s suffrage. The appeal of a community where everyone agreed to live collectively, making decisions jointly as to how they would spend their time and money and how to share responsibilities seemed like a paradise to many.

One of the loudest socialist voices in the US was Julius Wayland, a publisher from the Midwest who had become radicalized by pamphlets he had received from an Italian. His periodical The Coming Nation became the most popular socialist newspaper in the country. In 1893, inspired by John Ruskin, an English social critic, and Edward Bellamy’s utopian novel Looking Backward, Wayland established the first Marxist-inspired settlement in the US with the help of Isaac Broome, a well-known sculptor. The idea was to set up a cooperative village which would be supported by the proceeds of the newspaper.

Land was chosen in Dickson County, TN, first in a location that proved to have poor soil, before settling into 1,800 acres a few miles away, with beautiful natural surroundings and a large cave. Wayland named the colony the Ruskin Co-operative Association (RCA), and those who flocked to the site became known as Ruskinites. As a former farm with 600 tillable acres, it was perfect for the main industry of food production, and the cave and its spring were ideal for food canning and storage and a fresh water supply. There was a sawmill, machine shop, a bakery, steam laundry, grist mill, commissary, and the creation of products like chewing gum, cereal coffee and suspenders. A printing and publishing company was formed primarily for Wayland’s paper which would be printed weekly. For social activities there was a drama troupe and band, a cave entrance for parties, and communal areas like a kitchen, café and dining room. In all there were 75 buildings by 1897!

The idea was to create a cooperative commonwealth. Work was expected to be 50 hours a week and the members received “hour checks” for one-half of the time they worked, or a 25-hour check. If the members were children, women who were nursing a child or caring for others, or was a man who was unable to work they would receive an allowance in the form of hour checks. The scrip was then used for goods at the store or towards labor, or they could receive US money at 2 cents on the dollar. Because this was a socialist commune all medical care, housing, meals and mending of clothes or shoes was free to all members and their families. From the start Wayland and Broome envisioned a utopia with education as a cornerstone; there was a school and what was to be the Ruskin College of the New Economy to improve the minds of the settlers. At its peak there were approximately 250 people living at Ruskin Cave, coming from 32 states and several European countries.

“The successful co-operative village furnishes more opportunities for economy, culture and amusement than any other village of its size. It creates neither beggars nor tramps, but, recognizing its duty toward dependents and defectives, it supports them in a rational way. It gives security of employment and of a livelihood. The intelligent and strong help those who are not so fortunate. It is in many respects like a large family and tends to restore some of the good features of medieval family life. It is, therefore, a subject worthy of further experiment by intelligent and successful business people. – “The Ruskin Cooperative Colony” – JW Braam, 1903

The Ruskin Experiment was bold and seemed unstoppable, but it wasn’t long before the dream began to crumble. What went wrong? To begin with, the colony had so many different socio-economic backgrounds that while they had common political leanings, their life experiences could be vastly different. Unlike Rugby’s Christian pre-requisite, there were many different religions and there was friction regarding beliefs. Ruskinites themselves couldn’t always understand the socialist concepts, and some of the members were actually anarchists who would have liked to be free of all rules and regulations. And while the idea was a cooperative, only the founding members of the colony voted on the affairs of the RCA. When other settlers demanded the right to vote alongside the founders, it is said the women in the colony also expected a vote, which seemed outrageous to the men. (On the list of settlers there is notably no mention of women’s names!) Manners fell by the wayside on all issues, and bullies pushed their agendas on the weakest. Those with little education did not value it for their children, and they were said to be allowed to run too freely. There was the talk of Free Love amongst the young and grown. Wayland found himself so discouraged by the drama and chaos that he turned over the entire colony and its paper to the Ruskinites and forfeited most of his portion of the $100K that was used to create Ruskin. With Wayland’s departure the colony soon found itself in an intense fight between one faction with more anarchist leanings vs. those with socialist dreams of political and economic independence. Two years of lawsuits between the factions and inept financial managers soon led to the colony’s demise. By 1899 Ruskin was bankrupt, and a small, committed group packed up and moved to land near Waycross, GA, also calling this settlement Ruskin. However, the experiment was done, a financial and idealistic disaster, and by 1901 it was officially dissolved.

“People who come to Ruskin have ideal expectations. Reading the “Coming Nation” and Utopian dreams, lead them to expect that everyone attracted to such a place would be ideal characters, with ideal culture and ideal manners. It would be natural to expect of the citizens of such a community a depth and research of thought and conversation that would render the social life paradisaical. Imagine the shock to this idyllic when expectation is wrecked by finding within this magic circle characters so deficient in manners as to be repulsive... so deficient in moral principle as to be outlaws... so besotted in ignorance as to be beyond hope... Imagination cannot picture the shock to such spiritual ideals, to find the colony a prison. Ruled by the despotism of ignorance. A place where the hell of dissatisfaction exists in every nook and corner. A place where the executive is the Czar ruling without law. If you don’t keep quiet, dance to our music and vote to our wishes you will be discriminated against in work and favors; put to the most disagreeable labor and kept there, with the object of disciplining you into silence. It is Siberia over again. ” Isaac Broome, The Last Days of the Ruskin Co-operative Association.

And what happened to Wayland? By all accounts he flourished, starting an even more successful paper, the Appeal to Reason, which published work by famous authors Jack London, “Mother” Jones, Eugene Debs and Upton Sinclair. Sinclair was commissioned by the paper to write a book about meatpacking workers in 1904, and his novel The Jungle is celebrated today for its expose that helped put safety regulations and unions into place. As for Ruskin's co-founder Isaac Broome, he went on to write “The Last Days of the Ruskin Co-operative Association,” where he lamented that perhaps in the plan to create a self-government they only came up with a worse plan than what they started with. He is best known as the first sculptor to work in the American ceramics industry and enjoyed many accolades.

Today you can visit Ruskin Cave to see the site for yourself. Only a few of the original buildings remain, but it is a beautiful wedding and event venue, with pollinator gardens and multiple event sites, including a waterfall! It is easy to see the appeal of the area for those bold pilgrims who wanted to start a new society within a democratic experiment. The Ruskin Cave’s website is a wealth of information, as are the Tennessee State Archives, and it is to the credit of former State Senator Doug Jackson that this historic and fascinating place has been restored and remembered.

If you'd like to read more about Ruskin or Rugby, the research guides at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville are a great source.

As I conclude this three-part series on Utopian societies, let’s reflect on the fact that nearly all experiments with intentional societies we've covered have failed, and remember that this is, in fact, the norm rather than the rule. It’s literally written into the definition of Utopia:

UTOPIA Definition & Meaning - Merriam-Webster, often capitalized:

1: a place of ideal perfection especially in laws, government, and social conditions

2: an impractical scheme for social improvement

3: an imaginary and indefinitely remote place

But we're human, and humans will always dream and scheme for something better. We wouldn't want it any other way! Thanks for digging into this fascinating topic with me, and if you haven't already, please explore Part 1: Religious Societies and Part 2, Black Utopias.

Comments